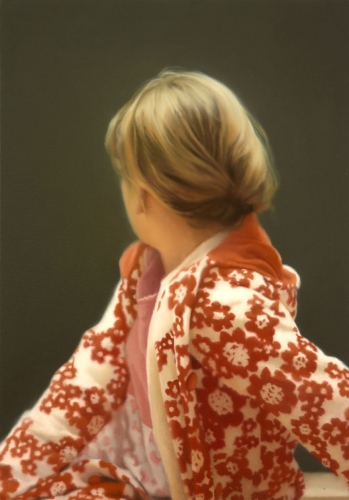

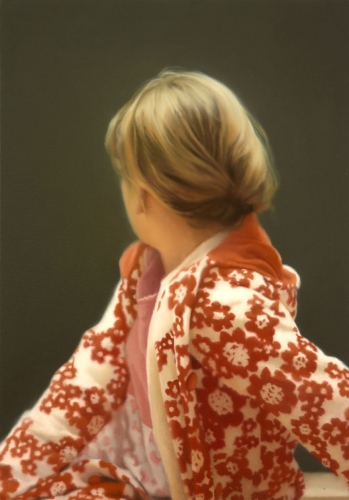

Gerhard Richter ha realizzato tre quadri che raffigurano la sua prima figlia Babette, detta Betty. I primi due sono del 1977, mentre l’ultimo del 1988. Il più famoso e il più amato è certamente il terzo (qui Robe da Chiodi ne propone un’interpretazione tanto audace e affascinante quanto legittima). Qui sotto li ripropongo in serie con i rispettivi fogli di Atlas che riportano le fotografie dai quali sono stati tratti. Il primo e il terzo sono esposti, ma in sale diverse, nella mostra “Panorama”, ora a Londra, poi a Berlino e Parigi (ne ho già scritto qui). Vederli così vicini fa un certo effetto. Non so spiegare quale, a dire il vero. Posso dire però due cose. La prima è che si vede in tutti e tre lo sguardo di un padre. Ciascuno esprime un sentimento diverso con il quale, immagino, un padre sia confrontato. La seconda è che Richter usa (sono tentato di dire “inventa”) tre differenti modi nuovi di realizzare un ritratto. Io dico che il più difficile da sostenere è il primo, non solo perché siamo confrontati con lo sguardo diretto di Betty. Sul terzo, quello famoso, riporto un brano del bel saggio di Achim Borchardt-Hume nel catalogo della mostra (p. 164):

In marked contrast, Betty, is resolutely looking back, albeit with the strong implication that she will soon be looking forward. The painting exudes a deep sense of nostalgia. Richeter’s adolescent daughter turns away from her father’s attempt to freeze her appearance with his camera. By extension, she also turns away from the present-day viewer. The typical Richter blur softens the painting’s photorealism and heightens the motif’s romantic aura (not unlike a photograph taken with a soft-focus lens). At the same time, it mimics the temporality oh photography, which, as Roland Barthes so aptly demonstrated, always entails a sense of loss, if not death, of something irretrievably gone.

Tutte le immagini sono tratte da www.gerhard-richter.com

In marked contrast, Betty, is resolutely looking back, albeit with the strong implication that she will soon be looking forward. The painting exudes a deep sense of nostalgia. Richeter’s adolescent daughter turns away from her father’s attempt to freeze her appearance with his camera. By extension, she also turns away from the present-day viewer. The typical Richter blur softens the painting’s photorealism and heightens the motif’s romantic aura (not unlike a photograph taken with a soft-focus lens). At the same time, it mimics the temporality oh photography, which, as Roland Barthes so aptly demonstrated, always entails a sense of loss, if not death, of something irretrievably gone.

All picture are taken from www.gerhard-richter.com