∑a mostra di Gerhard Richter Pictures/Series alla Beyeler di Basilea è una nuova occasione per ripetersi che, sì, esistono ancora grandi artisti e soprattutto grandi opere d’arte. Guardare, dopo aver visto il pittore tedesco, i Cézanne, i Monet, i Picasso, i Klee della collezione permanente conservata nel Museo progettato da Renzo Piano rinsalda nella certezza che, no, non tutto è perduto come alcuni dicono.

Eppure l’incontro con Richter non è mai facile, perché si tratta di un artista sfuggente, che fugge i tentativi dell’intelligenza di accalappiarlo. Appaga gli occhi, sfianca i neuroni. Non sappiamo bene dove ci porterà, che cosa ci sta dicendo, perché ce lo vuole dire. È qualcosa che ci attrae, di sicuro, e per questo il rovello che ci prende è ancor più intenso.

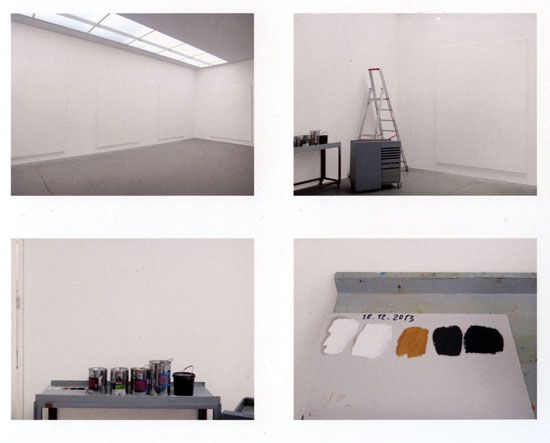

Qui però vorrei parlare del saggio che Georges Didi-Huberman ha scritto per il catalogo della mostra in forma di lettera allo stesso Richter. Parla di una visita, avvenuta nel dicembre del 2013, allo studio dell’artista. Dice: c’erano quattro tele bianche che attendevano di essere dipinte. Dice: l’arte di Richter vive di dubbio (ostilità verso tutte le forme di ideologia) e di desiderio. Il desiderio come motore del fare arte, che impedisce di arrendersi all’apparente assenza di significato delle cose. Dice: sono mesi che penso a che cosa accadrà di quelle tele bianche. Il critico francese ricorda quella risposta data a Nicholas Serota nell’intervista del catalogo di Panorama, in cui parla dell’impossibilità di raffigurare le immagini dell’olocausto. Ricorda che in quella risposta Richter cita un libro dello stesso Didi-Huberman Immagini malgrado tutto, che tratta proprio la possibilità di creare delle immagini dopo la tragedia dei campi di sterminio. Didi-Huberman racconta che una di queste immagini è appesa dello studio del pittore tedesco e che, andandolo a trovare e vedendo quelle quattro tele bianche ancora da dipingere ha pensato che forse, quello, sarebbe stato il luogo dove, finalmente, dopo sessant’anni di riflessione (c’è una foglio di Atlas dedicato), Richter avrebbe affrontato il tema più difficile. Ecco come termina la lettera:

«Spero che riuscirai a “portar fuori quelle immagini” dal tuo piano di montaggio psichico (troppo travolgente nell’immaginario), dove sono ancora da trovare, e da quel tuo piano di rappresentazione documentaria (troppo travolgente nel reale), dove noi forse le guardiamo. Non per sbarazzarcene, neanche per “salvarle attraverso l’arte”, ma invece, semplicemente per farle uscire e permettere che siano viste in modo diverso. So che quando uno ne ha abbastanza di qualcosa, in Germania voi dite: “Mi vien fuori dalla gola” (Es hängt mir zum Hals raus). In Francia noi diciamo: “Mi viene fuori dagli occhi” (Ça me sort par les yeux). Lasciaci attendere e vedere. Lasciaci vedere se queste immagini, alla fine, “ti verranno fuori attraverso gli occhi”, con l’aiuto della pittura».

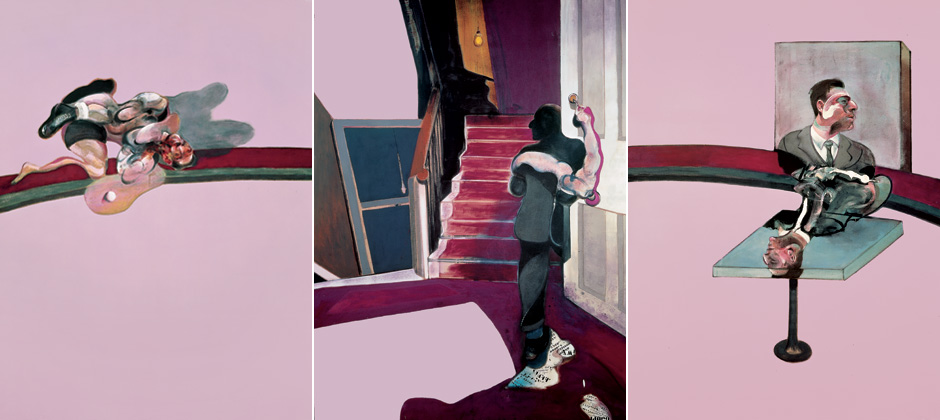

Qui qualche foto della mostra di Basilea (che nessuno mi ha impedito di fare)