Sono stato a Oxford a vedere la mostra di Jenny Saville di cui parlavo qualche post fa.

Un anno fa, nel suo blog, Jonathan Jones si domandava (lui diceva senza ironia) se la pittrice inglese fosse davvero tale o non fosse altro che un fenomeno un po’ strano di militanza femminista.

Io, per quello che può contare, non ho dubbi: Jenny Saville è una grande artista. Orfani di Lucian Freud, probabilmente, è la pittrice più importante in circolazione che si dedichi alla figura umana (ve ne vengono in mente altri?).

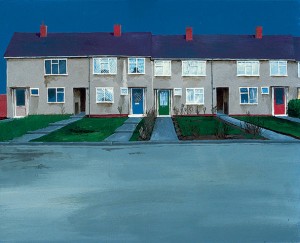

La mostra al Modern Art Oxford è una retrospettiva che ripercorre à rebours le tappe più significative della carriera dell’artista scoperta da Charles Saatchi. I primi quadri sono quelli dell’ultimo triennio, mentre nell’ultima stanza sono esposte le opere dei primi anni Novanta.

Quel che balza agli occhi è lo scarto che c’è stato in questo ultimo periodo in cui il lavoro sul corpo umano, da una sorta di ossessione per i volumi della carne, qui debordante, là ferita e deturpata, si trasforma in una riflessione sulla linea e sul movimento. Nel video in mostra, come aveva fatto nell’intervista che avevo segnalato, la Saville dice che ciò che le ha fatto cambiare marcia è stata l’esperienza della maternità. Dopo aver avuto due figli a distanza ravvicinata, l’artista racconta che è mutata in lei la percezione del proprio corpo. I nuovi quadri, infatti, sono di nuovo degli autoritratti nei quali compaiono, questa volta, anche i suoi figli. Ma non solo. Il riferimento ai grandi dell’arte antica (Leonardo e Tiziano) diventa esplicito. Come se, per esprimere il proprio sguardo sul corpo umano, la Saville avesse bisogno di tornare a questi grandi. Come se, per dire la scoperta della maternità, avesse bisogno di tornare là dove più compiutamente il rapporto tra madre e figlio era stato messo in scena. Questo aspetto è reso ancor più chiaro dallo spin off della mostra al Ashmolean Museum dove due sue opere sono esposte nella sala della pittura italiana del Rinascimento.

Il confronto con questi grandi sembra riuscirle senza cadere nel ridicolo, secondo, perché riesce a non dimenticarsi neppure della lezione di Bacon, ma forse ancor di più di quella di Picasso.

L’immagine qui sopra è un particolare del grande quadro “Mirror” che vedete qui sotto per intero. Il riferimento esplicito è alla Venere di Urbino di Tiziano.

I went to Oxford to see the exhibition of Jenny Saville I mentioned a few posts ago.

A year ago, in his blog, Jonathan Jones wondered (he said without irony) if the English painter was really an artist or she was nothing more than a strange phenomenon of feminist activism.

For what it’s worth, I have no doubt: Jenny Saville is a great artist. Orphans of Lucian Freud, she is probably the most important painter in circulation, which is devoted to the human figure (you can think of others?).

The exhibition at Modern Art Oxford is a retrospective covering a rebours the most significant stages of the career of the artist discovered by Charles Saatchi. The first pictures are those of the last three years, while the last room displays works of the early nineties.

What leaps to the eye is the gap that there was in this last period in which the work on the human body, a sort of obsession with the volumes of meat, overflowing here, wounded and disfigured there, it becomes a meditation on line and movement. In the video in exhibition, as she had done in the interview that I had indicated, Saville says that what changed her way of working has been the experience of motherhood. After having two children at close range, the artist says that perception of her body has changed in her. The new paintings, in fact, are still self-portraits in which, this time, even her children appear. But not only. The reference to the great ancient art (Leonardo and Titian) becomes explicit. As if to express her vision of the human body, Saville needed to go back to these great masters. As if to express the discovery of motherhood, she needed to go back there where more fully the relationship between mother and son had been staged. This is made even clearer by the spin-off show at the Ashmolean Museum, where two of his works are exhibited in the hall of Italian Renaissance painting.

The comparison with these great masters seems to succeed without ridicule. She can also not even forget the Bacon’s lesson, but perhaps even more Picasso’s one.

The image above is a detail of the big painting “Mirror” that you see below in full. The explicit reference is the Venus of Urbino by Titian.