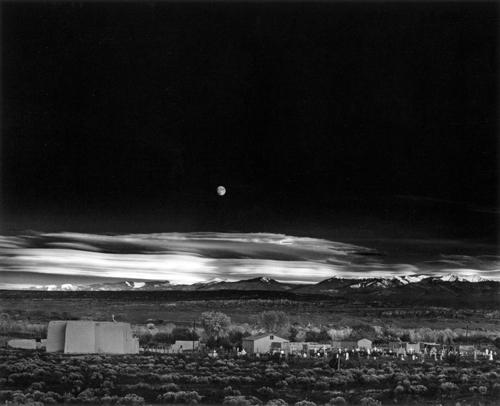

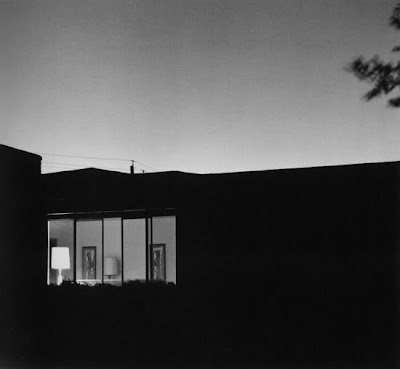

Mi è venuto in mente il NO di Mario Schifano. Guardando queste immagini pubblicate sull’ultimo numero di Aperture mi è parso di percepire lo stesso moto di rabbia. Forse meno selvaggio, ma ugualmente potente. Thomas Barrow è un artista che ha fatto della sperimentazione fotografica la sua cifra stilistica e nel bel mezzo degli anni Settanta realizza questa serie di foto intitolata Cancellations. Sono immagini in bianco e nero del paesaggio urbano americano, simili a quelle diventate celebri con la mostra del 1975 New Topographics: Photographs of Man-Altered Landscape. C’è un’unica differenza: l’immagine è sempre attraversata da una X ottenuta incidendo il negativo. Chi si ricorda che cos’è la fotografia tradizionale sa che tipo di violenza è nei confronti di un’immagine analogica un gesto del genere. Una cicatrice, uno sfregio ineliminabile. Un gesto apparentemente banale, quasi infantile. Eppure così carico di rabbia verso ciò che appare come un’ingiustizia. Tanto hanno riflettuto i fotografi americani su quell’aggettivo “man-altered” (penso a Robert Adams, Richard Misrach o Edward Burtynsky), eppure in loro ricerca della “wilderness” perduta aveva la forma di un’amara nostalgia. Barrow invece si ribella: si avventa con foga distruttrice facendo scempio dello scempio. Giovanni Testori, forse l’avrebbe chiamata “rivolta”. Un modo per urlare: “NO”.

I came up with NO by Mario Schifano. Looking at these pictures published in the current issue of Aperture I almost felt the same surge of anger.. Perhaps less wild, but equally powerful. Thomas Barrow is an artist who has worked extensively on photographic experimentation and, in the middle of the seventies, makes this series of photos entitled Cancellations. They are images of the American urban landscape in black and white, similar to those became famous in 1975 with the exhibition New Topographics: Photographs of Man-Altered Landscape. There is one difference: the image is always crossed by a X obtained by etching the negative. Who remembers what traditional photography is, knows what kind of violence is against analog image such a gesture. A scar, an ineliminable slash. Something as apparently trivial, almost childlike. Yet a gesture so full of anger at what appears to be an injustice. The American photographers have thought a lot about the adjective “man-altered” (I think of Robert Adams, Richard Misrach and Edward Burtynsky), yet in their quest for the lost “wilderness” was in the form of a bitter nostalgia. Barrow instead rebels: pounced eagerly making havoc of the havoc. Giovanni Testori, perhaps, would call “revolt”. A way to shout “NO”.