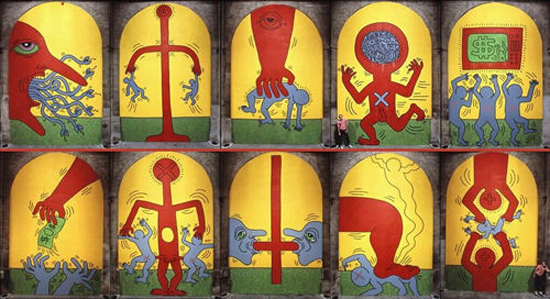

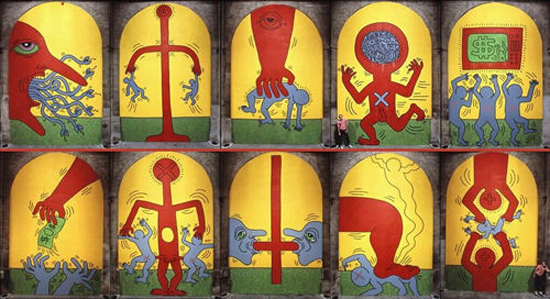

Il 2 settembre a Udine apre la mostra Keith Haring Extralarge – The Ten Commandments, The Marriage of Heaven And Hell a cura di Gianni Mercurio. Non sono un fan di Haring, però questa cosa dei dieci comandamenti mi ha subito incuriosito. E sono andato a leggere un po’. Tutto mi sarei aspettato tranne che scoprire che il tema religioso in Haring non è affatto episodico o casuale. Di famiglia protestante, l’artista si avvicina durante l’adolescenza al Jesus Movement, i cui membri erano chiamati Jesus People o Jesus Freaks (il primo capitolo di questa tesi spiega bene la vicenda). Haring prenderà la sua strada, ma i riferimenti alla religione continueranno a emergere nella sua arte. L’esempio più semplice è quello della sua “tag”: nel Radiant Child molti vedono la figura di Gesù Bambino.

Non siamo qui a battezzare nessuno. Per carità. È un fatto, però, che l’ultima opera di Haring sia una pala d’altare in bronzo ricoperta da foglia d’oro bianco. Oggi due dei multipli dell’opera The Life of Christ sono conservati nell’AIDS Interfaith Chapel della Grace Cathedral a San Francisco e nella St. Savior’s Chapel nella cattedrale episopale St. John The Divine nell’East Broadway. Ecco come nel 1990 Sam Havadtoy, artista e amico di Haring, racconta come nacque l’ultima opera del graffittaro più famoso della storia.

Nel 1989, Keith mi chiese di aiutarlo a decorare il suo nuovo appartamento a Manhattan. Nel salotto c’era un vecchio camino di mattoni che lui detestava, e così lo feci ricoprire di gesso. Mentre il gesso era ancora bagnato, suggerii a Keith di disegnarci sopra. L’idea gli piacque. Era come se il gesso fosse una tela tridimensionale. Gli piacque disegnare sul gesso, si esaltò moltissimo all’idea di questo nuovo medium. Quando ebbe finito, il risultato era stupendo. Allora gli proposi di fare un’edizione del camino e l’idea di nuovo gli piacque. Più tardi gli chiesi se volesse fare anche altri lavori in quel modo, magari dei pannelli o dei tavoli. Rise. Ma disse che gli sembrava una buona idea, e che l’avrebbe fatto.

Facemmo fare dei calchi per i panneli e per i tavoli, mi venne anche un’ispirazione all’ultimo minuto e cosi feci fare dei calchi speciali fatti a forma di icona russa, una pala d’altare, la versione ingrandita di una piccola icona che avevo visto in un negozio a Ginevra. Tutti i calchi furono portati in una quieta stanza, una sorta di utero materno, nel Dakota. Furono riempiti di creta fresca. Keith arrivò. Infilò una cassetta nel suo ghetto blaster, alzò il volume e sorseggiando una Coca si preparò a lavorare.

Invece del pennello, per la prima volta usò una spatola. Maneggiava la spatola in modo del tutto libero e spontaneo, come se stesse brandendo i suoi pennelli. Man mano che lavorava cominciò a prenderci sempre più gusto. Disse che gli sembrava impossibile che gli ci fosse voluto così tanto per scoprire questo tipo di scultura. Non fece alcun disegno preliminare, solo uno schizzo veloce del ballerino sul terzo pannello, che realizzo su un pezzo di legno cinque centimetri per dieci. Le immagini arrivavano direttamente dalla sua testa. Infilò la spatola nella creta e scolpì una linea ininterrotta, un solco profondo 6 mm e mezzo, che si snoda come un ruscello in piena durante il disgelo primaverile. Non si fermò mai a ripensare la linea, non si fermò a rivederla, non fece alcuna correzione. Le linee che tracciò nella creta erano perfette, senza alcuna interruzione. Keith finì i pannelli e poi per la prima volta vide le tre parti di altare. Le guardò a lungo in silenzio. Poi cominciò a lavorare. Infilò il coltello nella creta e cominciò a incidere linee curve. Le immagini che emersero erano diverse dalle altre. Erano religiose: una scena ispirata alla vita di Cristo, una bambino che, sostenuto da due mani, ascendeva al cielo, Cristo in croce. Su un lato del pannello scolpì la resurrezione. Sull’altro, un angelo caduto. Quando Keith ebbe finito, fece qualche passo indietro, guardò con attenzione il suo lavoro e disse: “Diavolo, questa si che è roba forte”. Quando finì di lavorare era esausto, e per la prima volta mi resi conto di quanto fosse diventato fragile. Era assolutamente senza fiato. Disse: “Mentre sto lavorando mi sento bene, ma appena smetto, mi piomba tutto addosso”.

La pala d’altare fu l’ultima opera di Keith.

The exhibition Keith Haring Extralarge The Ten Commandments – The Marriage of Heaven and Hell by Gianni Mercurio opens in Udine on September 2. I’m not a Haring’s fan, but the idea of Ten Commandments immediately intrigued me. I went to read around. Everything I expected except discover that the religious theme in Haring is not episodic or random. Born in a Protestant family, the artist approaches during adolescence in Jesus Movement, whose members were called Jesus People or Jesus Freaks (the first chapter of this dissertation explains the story). Haring take his own way, but the references to religion will continue to emerge in his art. The simplest example is his “tag”: the Radiant Child, in which many see the image of the Baby Jesus.

We are not here to baptize anyone. It is a fact, however, that Haring’s last work is an altarpiece cast in bronze with white gold leaf patina. Two of the editions of The Life of Christ can be seen in AIDS Interfaith Chapel of Grace Cathedral in San Francisco and St. Savior’s Chapel in the Cathedral of St. John The Divine in East Broadway. Here’s how Sam Havadtoy, an artist and Haring’s friend, in 1990 tells how the work was born.

In 1989, Keith asked me to help him decorate his new Manhattan apartment. In his living room was an old brick fireplace which he hated, so I had it plastered over. The plaster was wet and I suggested that he draw into it. He thought it was a cool idea. It was as if the plaster were a three-dimensional textured canvas. He loved drawing in the plaster, and got very excited about the new medium. When he finished, it was very beautiful. I asked him if he wanted to make an edition of the fireplace and he loved the idea. Later, I asked him if he wanted to do other works in editions — perhaps, panels and tables. He laughed. But he said he liked the idea — he would do it.

Trays were made for the panels and tables. I also had a last-minute inspiration and had special trays made in the shape of a Russian icon, an altar piece, a large version of a miniature icon I saw in a shop in Geneva. All the trays were then laid out in a quiet, womblike room in the Dakota. Trays were filled with fresh clay. Keith arrived. He snapped a tape into the ghetto blaster, turned up the music, sipped a Coke and set to work.

Instead of a brush, for the first time, he used a loop knife. He handled the knife freely and spontaneously like he wielded his brushes. As he worked, he became more and more excited. He said that he couldn’t believe it had taken him so long to discover this kind of sculpture. He made no preliminary drawings except for a quick sketch of the dancer on the third panel, which he made on a two-by-four piece of wood. Yet he was completely sanguine as he cut into the clay. The images came directly from his head. He placed the knife in the clay and carved a continuous running line, a quarter-of-an-inch deep groove, which wound like a swollen stream during the spring thaw. He never stopped to rethink the line; he never edited himself and never made corrections. The lines he carved in the clay were seamless, flawless.Keith finished the panels and then, for the first time, saw the three altar piece sections. He stared at them and was silent. Then he set to work. He cut into the clay and began to carve freeflowing lines. The images that emerged were unlike the others. They were religious: an inspiration of the life of Christ; a baby held by a pair of hands; hands ascending toward heaven; Christ on the cross. On one side panel he depicted the resurrection. On the other, a fallen angel. When Keith finished, as he stepped back and gazed at this work, he said, “Man, this is really heavy.” When he stopped, he was exhausted, and it was the first time I realized how frail he had become. He was completely out of breath. He said, “When I’m working, I’m fine, but as soon as I stop, it hits me . . . ”

The altar was Keith’s final piece of work.