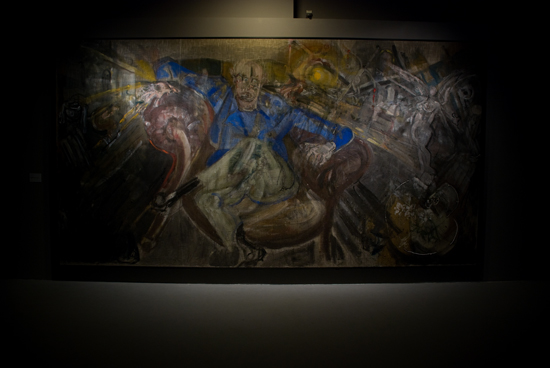

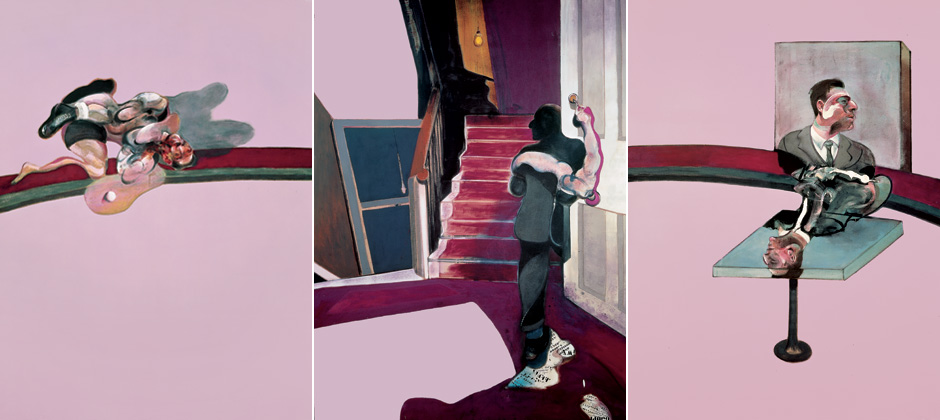

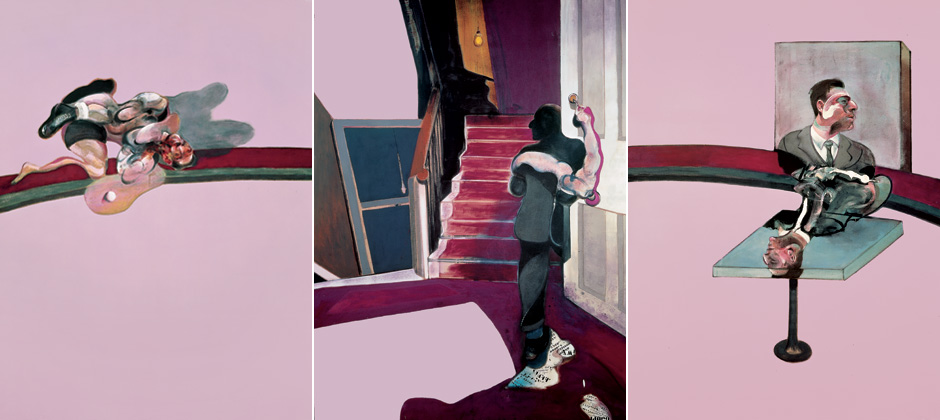

Un modo per parlare della mostra su Edgar Degas alla Fondazione Beyeler di Basilea è partire dalla fine. E cioè dalla sala che segue l’ultima stanza della mostra. Qui sono esposte tre opere di Francis Bacon (In memory of George Dyer, 1971; Portrait of George Dyer riding a bicycle, 1966 e Sand dune, 1983), una di Auguste Rodin (Iris, messagère des dieux (figure volante), 1890/91) e una di Lucio Fontana (un Concetto spaziale in terracotta simile a questo). L’effetto “doccia scozzese” che procura questa sala aiuta, con il suo shock, a toglierci di dosso la lettura che saremmo portati a sulle opere dell’ultimo Degas (tema della mostra). Invece guardare Degas con gli occhi di Bacon è un esercizio salutare perché spoglia il pittore francese da una possibile lettura “piccolo borghese”. Non è un mistero che Bacon amasse Degas e lo considerasse uno dei suoi artisti di riferimento. Ne parlò diverse volte con David Sylvester e, in un’occasione, Bacon indica come il miglior Degas proprio quello dei pastelli a cui la mostra di Basilea è quasi interamente dedicata:

«The very great Degas are the pastels, and don’t forget that in his pastels he always striates the form with these lines which are drawn through the images and in a certain sense both intensify and diversify its reality. I always think that the interesting thing about Degas is the way he made line throught the body: you could say the he shuttered the body, in a way, shuttered the image and then he put an enormous amount of color through these lines. And having shuttered the form, he created intensity by this colour through the flesh».

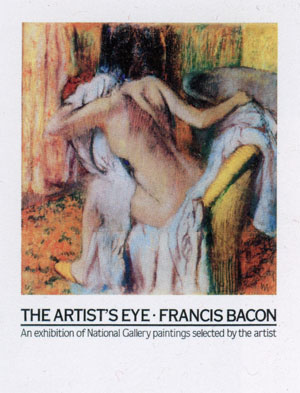

Quando poi la National Gallery nel 1985 invitò Bacon a curare una mostra della serie “The artist’s eyes”, in cui un artista contemporaneo faceva una selezione delle opere della collezione, sulla locandina e sulla copertina del catalogo ci finì proprio un pastello di Degas. Il curatore Martin Schwander in catalogo lo dice chiaramente: uno degli artisti che condivise con Degas la visione del corpo umano come il campo di battaglia di forze invisibili fu Francis Bacon. Sul rapporto tra i due pittori, tra l’altro, ha scritto anche Martin Hammer in saggio frutto di una conferenza alla Tate Britain lo scorso 24 novembre 2011. Il testo lo trovate qui.

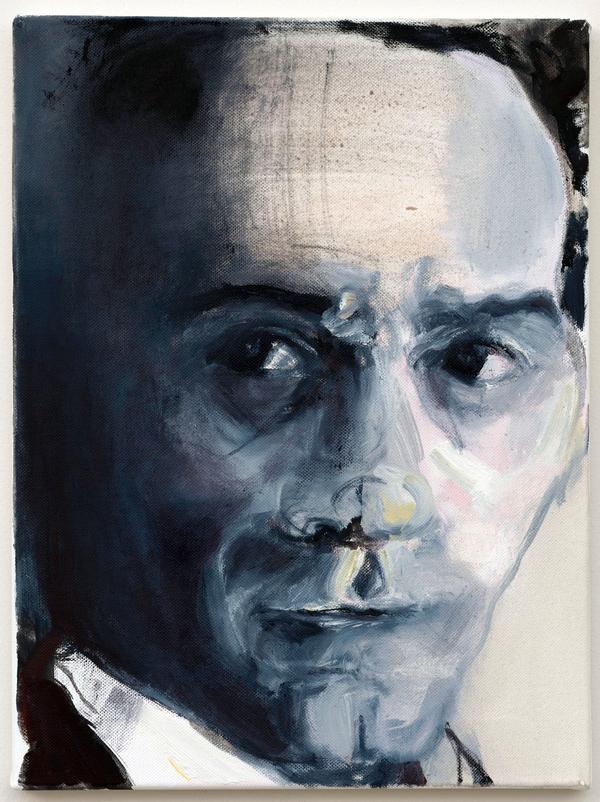

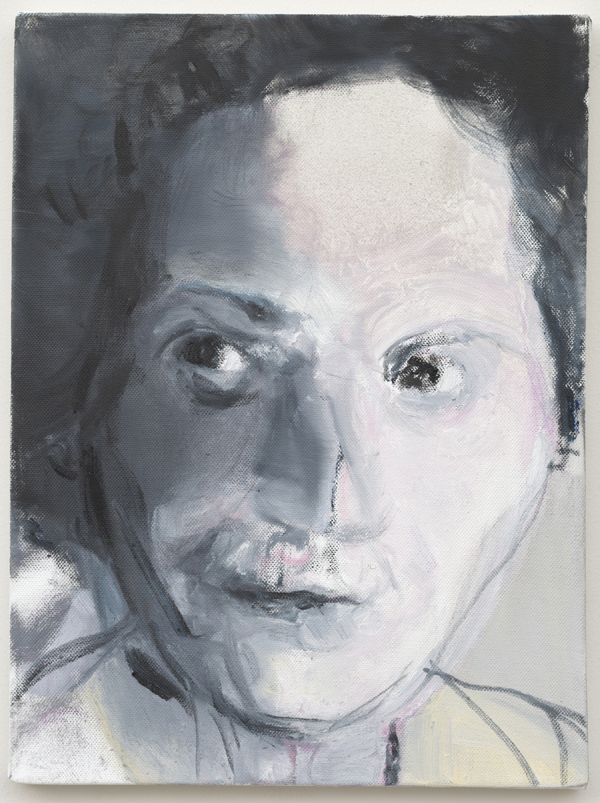

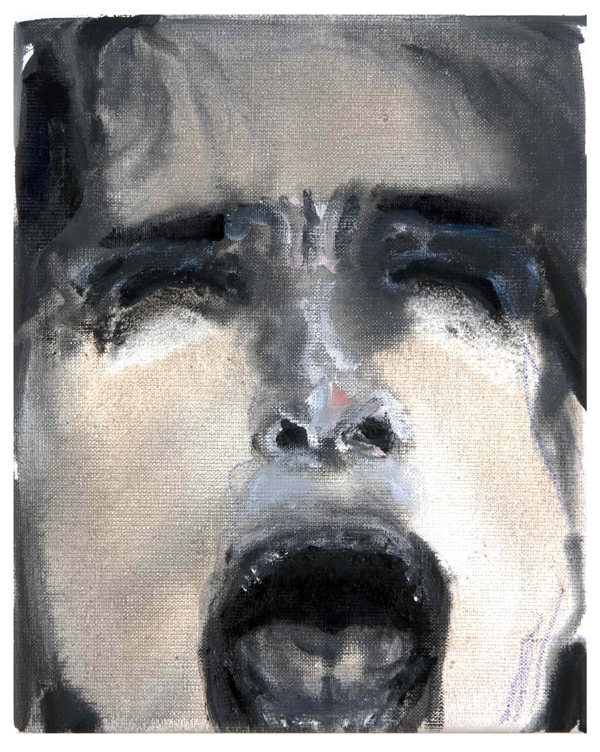

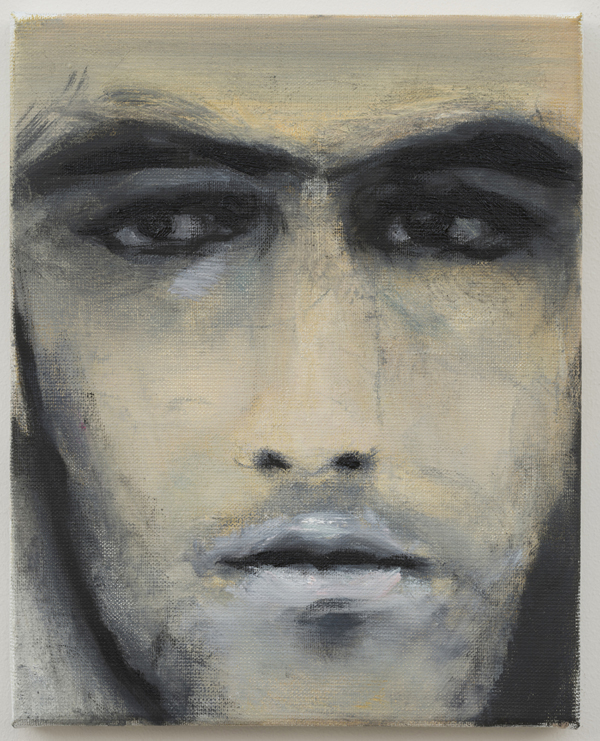

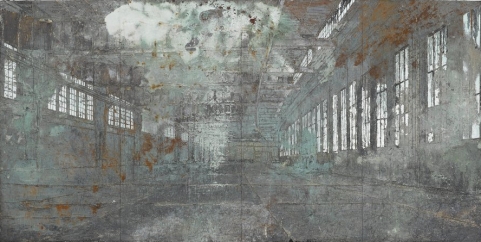

In mostra in almeno un punto i ruoli sembrano invertirsi: è Degas a guardare Bacon:

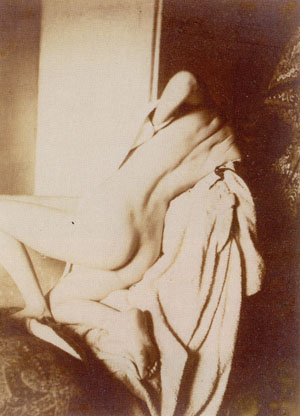

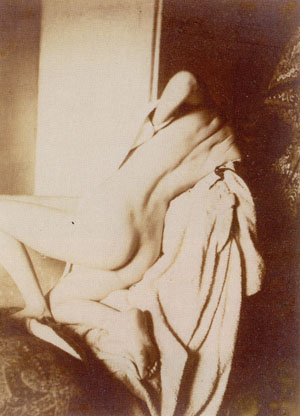

Un quadro davvero forte e profondamente novecentesco. Forse non è un caso che nasca da una fotografia scattata dallo stesso Degas:

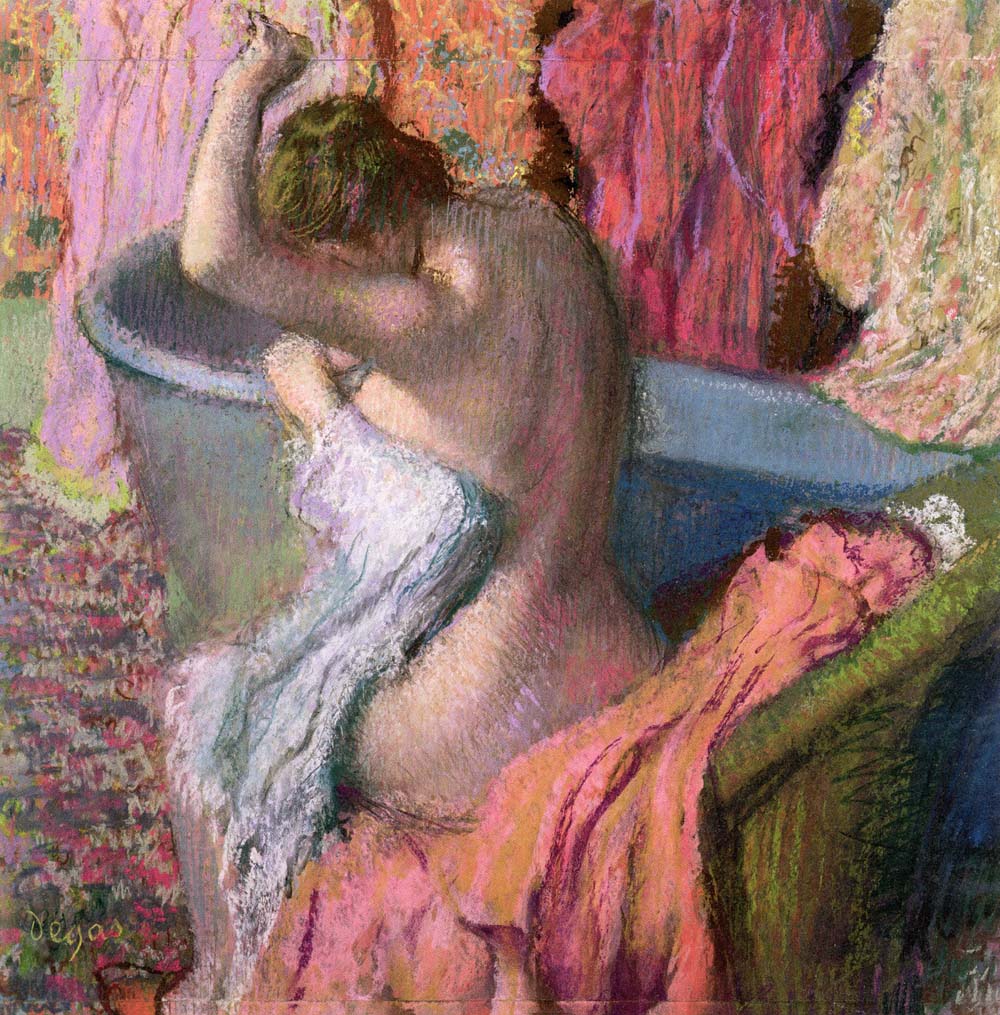

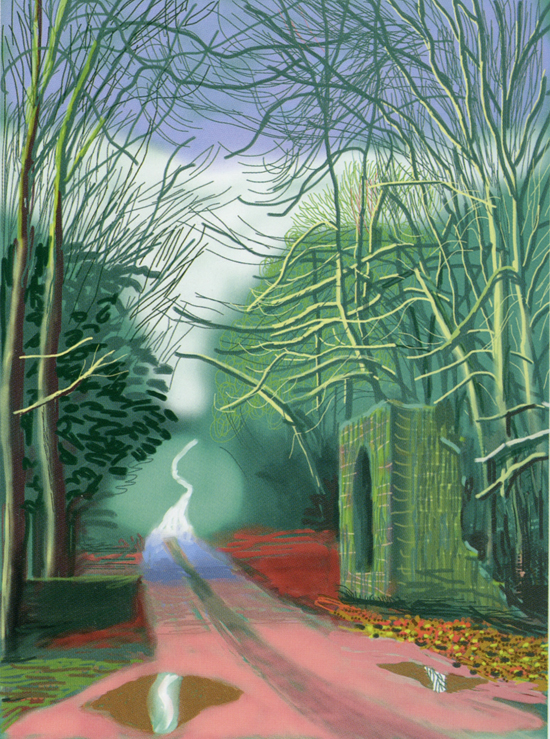

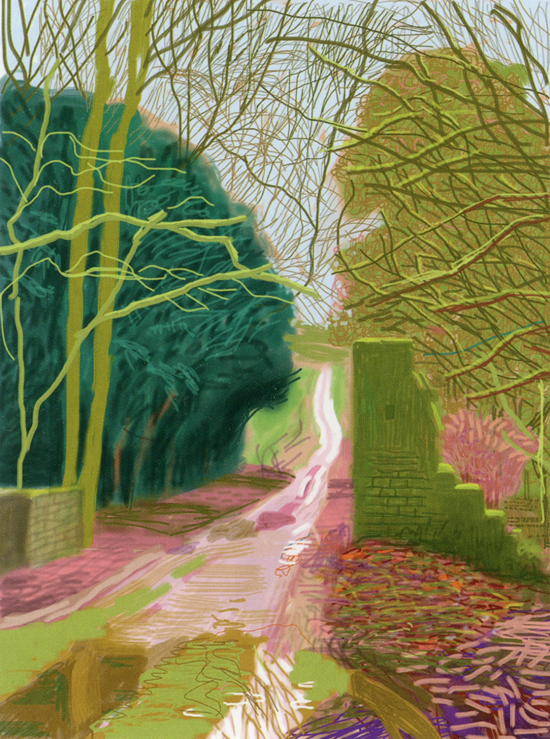

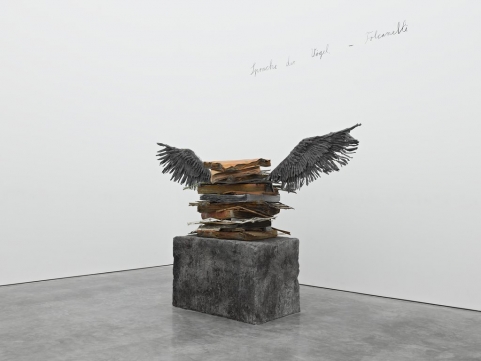

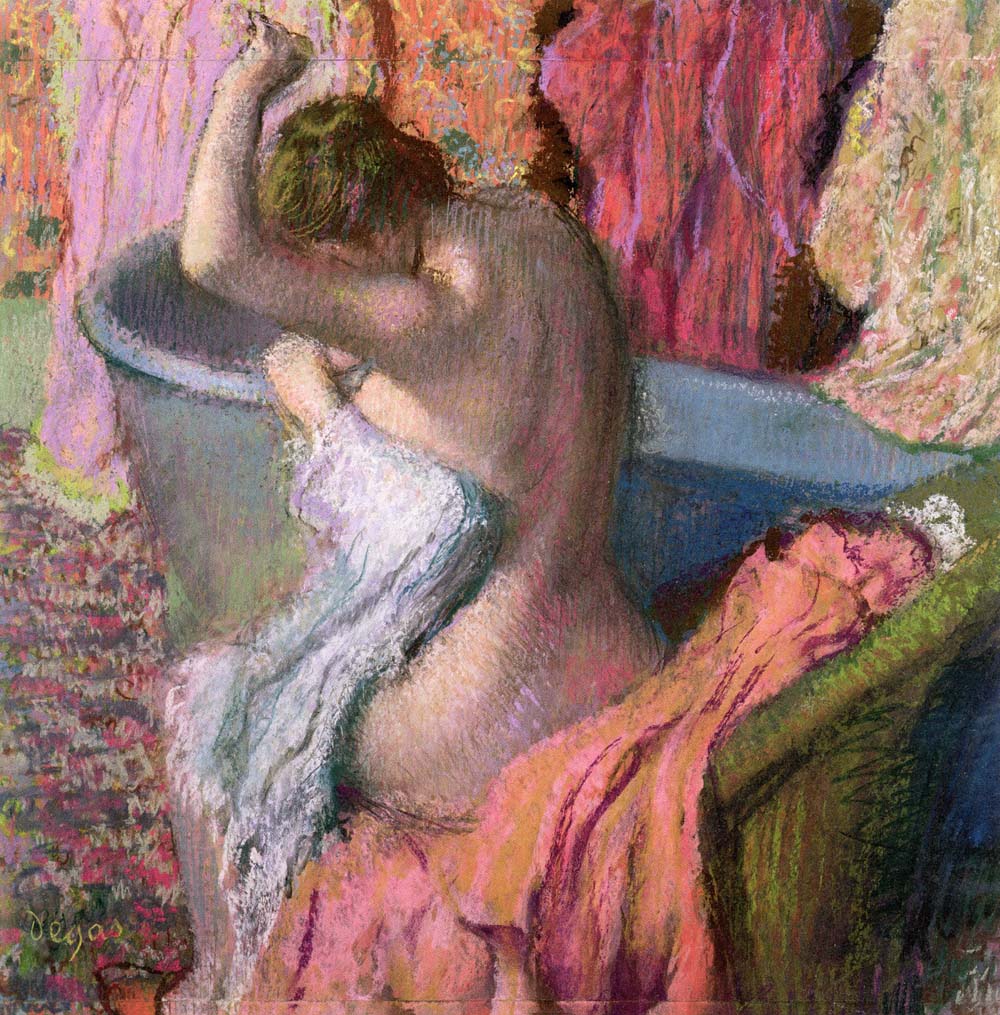

Comunque, se avessi potuto portarmi a casa un quadro mi sarei portato a casa questo qui sotto. Quella torsione michelangiolesca e quei colori pop sono davvero irresistibili.

One way to talk about the exhibition on Edgar Degas at the Beyeler Foundation in Basel is starting from the end. I mean from the room that follows the last room of the exhibition. Here are exhibited three works by Francis Bacon (In memory of George Dyer, 1971; Portrait of George Dyer riding a bicycle, 1966 e Sand dune, 1983), one by Auguste Rodin (Iris, messagère des dieux (figure volante), 1890/91) and one by Lucio Fontana (a Concetto spaziale similar to this one). The effect of “cold shower” that provides this room helps us, with his shock, to take off the reading that would be carried on the works of the last Degas (theme of the show). Instead looking Degas through Bacon’s eyes is a healthy exercise that strips the French painter from a possible “petty bourgeois” reading. It is no secret that Bacon loved Degas and considered him one of his artists to reference. It is no secret that Bacon loved Degas and considered him one of his artists to reference. He spoke several times with David Sylvester and, on one occasion, Bacon says:

«The very great Degas are the pastels, and don’t forget that in his pastels he always striates the form with these lines which are drawn through the images and in a certain sense both intensify and diversify its reality. I always think that the interesting thing about Degas is the way he made line throught the body: you could say the he shuttered the body, in a way, shuttered the image and then he put an enormous amount of color through these lines. And having shuttered the form, he created intensity by this colour through the flesh».

Then, when the National Gallery in 1985 Bacon invited to curate an exhibition of the series “The artist’s eyes”, in which a contemporary artist made a selection of works from the collection, on the poster and on the cover of the catalog was placed right a pastel by Degas. The curator Martin Schwander in catalog makes it clear: one of the artists who shared with Degas the vision of the human body as the battleground of invisible forces was right Francis Bacon. On the relationship between the two artists, among others, also Martin Hammer wrote essay fruit of a conference at Tate Britain on 24 November 2011. The text can be found here.

On show at one point the roles seem reversed: it is Degas to look Bacon:

A picture really strong and deeply twentieth century. Perhaps it is no coincidence that spring from a photograph taken from Degas himself:

However, if I could bring home a painting I would have taken home this below. That Michelangelesque twist and those pop colors are truly irresistible.