Il cardinal Gianfranco Ravasi ha annunciato la sua intenzione di portare un Padiglione della Città del Vaticano alla Biennale di Venezia ormai qualche anno fa. Previsto per l’edizione del 2011, fu posticipato a data da destinarsi. Forse nel 2013. Quando gli chiesi informazioni nell’autunno del 2010 mi rispose che non c’erano i tempi tecnici per arrivare pronti al 2011. Ma da come parlava sembrava che l’idea ci fosse, ma fosse difficile da realizzare. La vera verità è che, a febbraio 2012, non sembra esserci neppure l’idea. Per ora sembra che il cardinale abbia riunito nel dicembre scorso un ipotetico comitato scientifico che potrebbe occuparsi del progetto. Ne farebbero parte Sandro Barbagallo, critico d’arte dell’Osservatore Romano, Micol Forti, direttore della Collezione d’arte contemporanea dei Musei vaticani, Francesco Buranelli, già direttore dei Musei vaticani e oggi segretario della Pontificia Commissione per i Beni culturali e padre Davide Dall’Asta, direttore della Raccolta Lercaro di Bologna. Il comitato, trapela da voci nei corridoi vaticani, in teoria dovrebbe occuparsi di realizzare le direttive suggerite da Ravasi. Ma sembra che in questo momento direttive non ce ne siano. Il gruppo di lavoro si sarebbe dovuto incontrare di nuovo a gennaio. Ma ai quattro le convocazioni non sono arrivate. Allo stato delle cose, dunque, oltre alle dichiarazioni via stampa di Ravasi non sembra esserci nulla di concreto. E il Padiglione vaticano alla Biennale resta un miraggio.

Il cardinal Gianfranco Ravasi ha annunciato la sua intenzione di portare un Padiglione della Città del Vaticano alla Biennale di Venezia ormai qualche anno fa. Previsto per l’edizione del 2011, fu posticipato a data da destinarsi. Forse nel 2013. Quando gli chiesi informazioni nell’autunno del 2010 mi rispose che non c’erano i tempi tecnici per arrivare pronti al 2011. Ma da come parlava sembrava che l’idea ci fosse, ma fosse difficile da realizzare. La vera verità è che, a febbraio 2012, non sembra esserci neppure l’idea. Per ora sembra che il cardinale abbia riunito nel dicembre scorso un ipotetico comitato scientifico che potrebbe occuparsi del progetto. Ne farebbero parte Sandro Barbagallo, critico d’arte dell’Osservatore Romano, Micol Forti, direttore della Collezione d’arte contemporanea dei Musei vaticani, Francesco Buranelli, già direttore dei Musei vaticani e oggi segretario della Pontificia Commissione per i Beni culturali e padre Davide Dall’Asta, direttore della Raccolta Lercaro di Bologna. Il comitato, trapela da voci nei corridoi vaticani, in teoria dovrebbe occuparsi di realizzare le direttive suggerite da Ravasi. Ma sembra che in questo momento direttive non ce ne siano. Il gruppo di lavoro si sarebbe dovuto incontrare di nuovo a gennaio. Ma ai quattro le convocazioni non sono arrivate. Allo stato delle cose, dunque, oltre alle dichiarazioni via stampa di Ravasi non sembra esserci nulla di concreto. E il Padiglione vaticano alla Biennale resta un miraggio.

E fin qui la cronaca. Ecco invece tre possibili scenari che mi pare potrebbero realizzarsi:

1) Versione clerical del padiglione Sgarbi

È già stata collaudata l’estate scorsa in occasione della mostra per il sessantesimo anniversario dell’ordinazione sacerdotale di Benedetto XVI. Una lista di un centinaio di artisti che alternava grandi nomi, illustri sconosciuti e personaggi al di sotto di qualsiasi sospetto. Ogni artista dona un’opera di sua scelta. Nessuna preoccupazione di organicità.

È già stata collaudata l’estate scorsa in occasione della mostra per il sessantesimo anniversario dell’ordinazione sacerdotale di Benedetto XVI. Una lista di un centinaio di artisti che alternava grandi nomi, illustri sconosciuti e personaggi al di sotto di qualsiasi sospetto. Ogni artista dona un’opera di sua scelta. Nessuna preoccupazione di organicità.

VANTAGGI: Facile da realizzare. Poco costosa. Accontenta gran parte del sottobosco artistico romano legato a cardinali e monsignori di curia. Poche polemiche in ambito cattolico.

SVANTAGGI: Basso profilo mediatico. Critiche degli esperti del settore.

2) Versione art chic del portico dei gentili

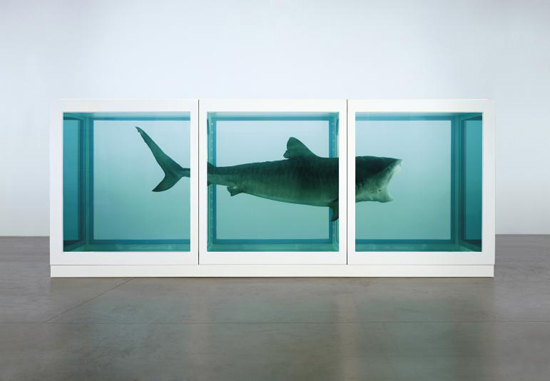

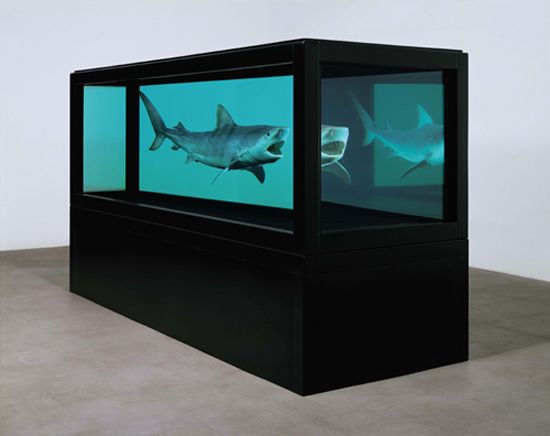

È l’idea paventata nell diverse interviste dallo stesso Ravasi che ne sarebbe il vero curatore. Nomi di respiro mondiale come Bill Viola, Anish Kapoor, Yanis Kounellis. Un bel tema ampio e biblico (il libro della Genesi). Libertà assoluta per gli artisti. Poche opere, ma di impatto.

VANTAGGI: Copertura mediatica globale. Plauso degli esperti del settore, dei collezionisti che contano e un servizio di sei pagine su Vogue. Poter dire che la Chiesa è tornata ad essere un interlocutore per l’arte che davvero conta.

SVANTAGGI: Difficile da realizzare (convincere gli artisti a partecipare). Costoso. Assicurata l’ondata di critiche del mondo cattolico. Necessità di un giubbotto antiproiettile per poter girare nei palazzi vaticani.

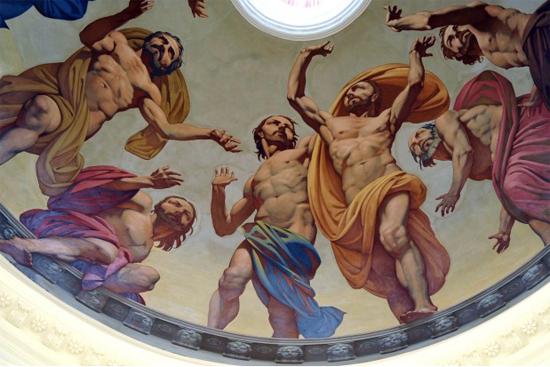

3) Versione cur(i)atoriale

Scegliere un curatore vero ma cattolico. Affidargli l’incarico di selezionare un gruppo ristretto di artisti di primo piano (da uno a cinque, non necessariamente di grido) in grado di mettersi in gioco in un progetto in cui il curatore possa dire davvero la sua. Quindi libertà dell’artista e libertà del curatore/committente. Come modello potrebbe essere presa l’esperienza dell’Evangeliario ambrosiano.

Scegliere un curatore vero ma cattolico. Affidargli l’incarico di selezionare un gruppo ristretto di artisti di primo piano (da uno a cinque, non necessariamente di grido) in grado di mettersi in gioco in un progetto in cui il curatore possa dire davvero la sua. Quindi libertà dell’artista e libertà del curatore/committente. Come modello potrebbe essere presa l’esperienza dell’Evangeliario ambrosiano.

VANTAGGI: Possibilità di dire che la Chiesa è tornata a fare committenza a alti livelli. Discreto impatto mediatico.

SVANTAGGI: Difficoltà nel reperire un curatore vero ma cattolico senza innescare faide. Critiche sia da parte cattolica che da parte degli esperti di settore. Discreto impatto mediatico.

Cardinal Gianfranco Ravasi announced its intention to bring the Vatican Pavilion at the Venice Biennale a few years ago. Scheduled for the edition of 2011, it was postponed until a later date. Maybe in 2013. When I asked him (it was the fall of 2010) he said that there were no technical time to get ready in 2011. But as he spoke, it seemed that there was the idea, but it was difficult to achieve. The real truth is that, in February 2012, there seems to be not even the idea. For now it seems that last December the cardinal had gathered a hypothetical scientific committee that could deal with the project. It would be part Sandro Barbagallo, art critic of the Osservatore Romano, Micol Forti, director of contemporary art collection of the Vatican Museums, Francesco Buranelli, former director of the Vatican Museums, and now secretary of the Pontifical Commission for Cultural Heritage and father David Dall’Asta, Director of Collection Lercaro of Bologna. The committee, leaked by voices in the corridors of the Vatican, in theory should take care to make the guidelines recommended by Ravasi. But it seems that at this moment there are no directives. The working group would have to meet again in January. But the four summonses have not arrived. As things stand, therefore, in addition to Ravasi’s statements in the press, there would be nothing concrete. And the Vatican Pavilion at the Biennale remains a mirage.

In the cardinal’s mind, we hope, are taking shape three possible scenarios to achieve what will be known as the Ravasi Pavilion:

1) Clerical version of the Sgarbi pavilion

It has already been tested last summer on the occasion of the exhibition for the birthday of Benedict XVI. A list of a hundred artists who alternated big names, illustrious unknown, people under any suspicion. Each artist donates a work of his choice. No worries of organicity.

PROS:

Easy to achieve. Inexpensive. Satisfied much of the roman art undergrowth related to cardinals of the Curia and monsignors. Some controversy in Catholic circles.

CONS: Basso profilo mediatico. Critiche degli esperti di arte.

2) Art-chic version of the arcade of the Gentiles

It’s the idea announced in several interviews by the same Ravasi who would be the true curator. Names of worldwide importance such as Bill Viola, Anish Kapoor, Yanis Kounellis. A nice wide biblical theme (the book of Genesis). Total freedom for artists. Few works, but impact.

It’s the idea announced in several interviews by the same Ravasi who would be the true curator. Names of worldwide importance such as Bill Viola, Anish Kapoor, Yanis Kounellis. A nice wide biblical theme (the book of Genesis). Total freedom for artists. Few works, but impact.

PROS:

Global media coverage. Praise of art experts, big collectors and six pages of Vogue. To say that the Church is once again a partner for great art.

CONS: Difficult to achieve (to convince the artists to participate). Expensive. Ensuredthe wave of criticism of the Catholic world. Need for a bulletproof vest to run in the Vatican.

3) Cur(i)atorial version

Choose a true curator but Catholic. Entrust the task of selecting a small group of leading artists (one to five, not necessarily ultra-cool) can get involved in a project in which the curator can really have a say. So artistic freedom and freedom of the curator. As a model could be taken the Evengeliario ambrosiano.

Choose a true curator but Catholic. Entrust the task of selecting a small group of leading artists (one to five, not necessarily ultra-cool) can get involved in a project in which the curator can really have a say. So artistic freedom and freedom of the curator. As a model could be taken the Evengeliario ambrosiano.

PROS: Opportunity to say that the Church is back to do commission in high levels. Poor media coverage.

CONS: Difficulty in finding a true curator but Catholic without triggering feuds. Criticism both from Catholics by art experts. Poor media coverage.